GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK

Gill & Lagodich has reframed a number of paintings in the Thannhauser Collection at the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum, New York City. Museum projects include both period and replica frames for artwork by Braque, Cézanne, Gauguin, Kandinsky, Klee, Manet, Matisse, Picasso, and Van Gogh, as well as restoration of a 17th-century frame from the museum collection for Van Gogh's Mountains at Saint-Remy.

GEORGES BRAQUE (1882 – 1963)

Landscape Near Antwerp (Paysage pres d'Anvers), 1906, oil on canvas, 23-5/8" x 31-7/8", custom-made replica frame, oxidized soft maple, inset radial corners, design and color matched to original frame in Musee D'Orsay. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser 78.2514.1

PAUL CÉZANNE (1839–1906)

La Route Tournante en Sous-bois (Bend in the Road Through the Forest), 1873-75, oil on canvas, 21-3/4 x 18-3/8 inches. Custom-made replica 18th-century Roman molding; hand carved and gilded wood, molding width 3-1/2 in. Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Partial gift, George Tetzel in memory of Oscar Homolka and Joan Tetzel Homolka, 1980

PAUL GAUGUIN (1848 – 1903)

Haere Mai, 1891, oil on burlap, 28-1/2" x 36", custom-made primitivist frame, hand-carved mahogany with antiqued-gesso flat wood liner. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978, 78.2514.16

PAUL KLEE (1879–1940)

Night Feast ( Nächtliches Fest ) , 1921, oil on paper, mounted on cardboard painted with oil, mounted on board; sheet: 14 1/2 x 19 5/8 inches (36.9 x 49.8 cm); mount: 19 3/4 x 23 5/8 inches (50 x 60 cm). Custom pyramid-profile frame based on original Klee design, made by Gill & Lagodich for Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832–1883)

Before the Mirror (Devant la glace), 1876, oil on canvas, 36-1/4 x 28-1/8 inches; late-19th-century Continental ebonized painting frame; dimensional molding with carved ripple and gilded hollow at sight edge; molding width: 6-5/16” "In 1865 Edouard Manet shocked Parisian audiences at the Salon with his painting Olympia (1863), an unabashed depiction of a prostitute lounging in bed, naked save for a pair of slippers and a necklace. While not an unpopular subject in 19th-century French painting, the courtesan had rarely been portrayed with such honesty. The artist provoked a similar scandal when his painting Nana (1877)—depicting a coquettish young woman in a state of partial undress powdering her nose in front of an impatient client—was exhibited in a shop window on the boulevard des Capucines. Manet’s attention to a motif conventionally associated with pornography reflected his desire to render on canvas the truths of modern life. It was a theme that symbolized modernity for many late-19th-century artists and writers, including Edgar Degas and Emile Zola, who devoted their work to realistic portrayals of the shifting class structures and mores of French culture. Images of courtesans may be found throughout Manet’s oeuvre; Before the Mirror is thought to be one such painting, related iconographically to Nana, but more spontaneous in execution. The artist’s vigorous brushstrokes lend an air of immediacy to the picture. As in Nana, the corseted woman represented here admires her reflection in a mirror; but this particular scene is extremely private—the woman, in quiet contemplation of her own image, is turned with her back to the viewer." —Nancy Spector. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832 – 1883)

Woman in Striped Dress, ca. 1877–80, oil on canvas, 69 1/8 x 33 3/16 inches (175.5 x 84.3 cm), framed by Gill & Lagodich, custom-made replica variation of c. 1900 French reverse profile painting frame gilded and toned to harmonize with painting: patinated 18.4 karat French Dauvet vert fonce gold leaf on varied bole and gesso substrate on applied cast ornament; patinated mahogany reverse; molding width: 5-1/4” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978 “In 1865 Edouard Manet shocked Parisian audiences at the Salon with his painting Olympia (1863), an unabashed depiction of a prostitute lounging in bed, naked save for a pair of slippers and a necklace. While not an unpopular subject in 19th-century French painting, the courtesan had rarely been portrayed with such honesty. The artist provoked a similar scandal when his painting Nana (1877)—depicting a coquettish young woman in a state of partial undress powdering her nose in front of an impatient client—was exhibited in a shop window on the boulevard des Capucines. Manet’s attention to a motif conventionally associated with pornography reflected his desire to render on canvas the truths of modern life. It was a theme that symbolized modernity for many late-19th-century artists and writers, including Edgar Degas and Emile Zola, who devoted their work to realistic portrayals of the shifting class structures and mores of French culture. Images of courtesans may be found throughout Manet’s oeuvre; Before the Mirror is thought to be one such painting, related iconographically to Nana, but more spontaneous in execution. The artist’s vigorous brushstrokes lend an air of immediacy to the picture. As in Nana, the corseted woman represented here admires her reflection in a mirror; but this particular scene is extremely private—the woman, in quiet contemplation of her own image, is turned with her back to the viewer. Manet’s endeavor to capture the flavor of contemporary society extended to portraits of barmaids, street musicians, ragpickers, and other standard Parisian “types” that were favorite subjects of popular illustrated literature. Since the subject of Woman in Striped Dress is unidentified—conjecture that she might be the French actress Suzanne Reichenberg remains purely speculative—it is tempting to view this portrait as Manet’s rendering of one such type: the fashionable Parisian bourgeois woman, complete with Japanese fan. Both paintings exemplify Manet’s use of seemingly improvised, facile brushstrokes that emphasize the two-dimensionality of the canvas while simultaneously defining form and space. From our vantage point, it is less Manet’s choice of subject matter than the tension between surface and subject, in which the paint itself threatens to dissolve into decorative patterns, that defines his work as quintessentially Modern.” —Nancy Spector

HENRI MATISSE (1869 – 1954)

Nude In A Forest (Nu dans un paysage ensoleille), 1909–12, oil on canvas, 16-1/2" x 12-3/4", custom-made replica Modernist frame, parcel gilt and patinated carved mahogany, cassetta profile. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 84.3252

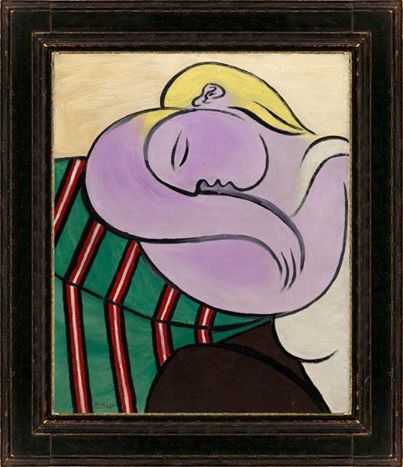

PABLO PICASSO (1881–1973)

"Woman With Yellow Hair (Femme Aux Cheveux Jaunes)", 1931, oil on canvas, 39-3/8" x 31-7/8" Custom-made replica reverse profile 17th-century Spanish plate frame, hand-carved from old wood, Douglas Fir, ebonized patina, wide dimensional profile. Molding width: 6”

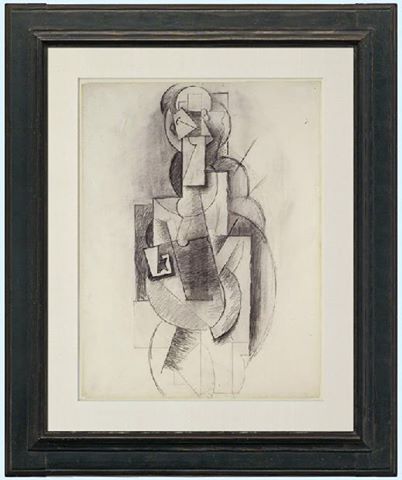

PABLO PICASSO (1881–1973)

Femme a la Guitare", 1913-14, graphite on paper. Custom made replica 17th-century Spanish plate frame, hand-carved from salvaged Douglas fir, ebonized patina.

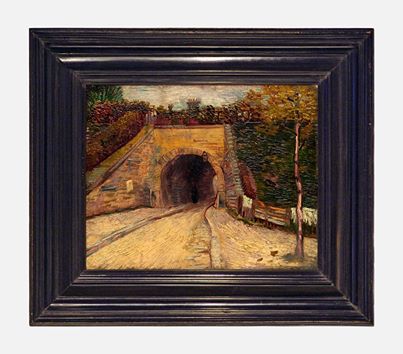

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853–1890)

“Roadway With Underpass (Le Viaduc)," oil on cardboard mounted on panel, 1887, 12-7/8” X 16-1/8” 19th-century European painting frame; Macassar ebony and ebonized pine, Molding width: 4-1/2" Period frame donated by Gill & Lagodich, 2010. "While living in Paris, Vincent van Gogh made frequent excursions to the suburb of Asnières to escape the urban environment and paint in nature before his subject, a method he often advocated to other artists. On these trips he would usually stay at the family home of Bernard, a young painter he advised. In a letter to Bernard from Arles, Van Gogh reiterated his position on the importance of painting from experience rather than from the imagination: “I am getting well acquainted with nature. I exaggerate, sometimes I make changes in a motif; but for all that, I do not invent the whole picture; on the contrary, I find it all ready in nature, only it must be disentangled.”¹ On a late summer day in 1887, the artist set out to record one of the many now-extinct poternes, or underpass and tollhouse structures, that ringed Paris and regulated entry into the city. For Roadway with Underpass (Le viaduc), Van Gogh chose the vantage point of a traveler en route from Asnières, which is suggested by a dim glow at the end of the tunnel. The lone figure clad in black walking into the darkness midway in the tunnel lends a vague air of foreboding. Van Gogh painted this scene at the beginning of his mature period when he was exploring the technical achievements of the various stylistic idioms current in Paris. The contrasting creamy ocher impasto and chalky blue shadows on the crumbling underpass and the road suggest the heightened palette and divided brushstroke of the Impressionists. Moreover the contrasting complementary colors he employs in the energetic dots and loose dashes that imply the movement of the foliage animated by the breeze on the embankment attest to his hesitant investigations of Divisionist color theory. Roadway with Underpass foreshadows two paintings with similar compositions that Van Gogh would paint in Arles in 1888: The Trinquetaille Bridge (Le pont de Trinquetaille) and The Railroad Bridge (Le pont de Languelois). Like the present painting, these two works present a view through a tunnel from the perspective of a spectator situated diagonally to the right of the bridge; however, the more complex later canvases also include a counterthrusting pathway leading to the left." —Jennifer Blessing 1. Vincent van Gogh to Bernard, October 1988, The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 3 (Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society, 1958), B19, p. 518. 2. Vivian Endicott Barnett, The Guggenheim Museum: The Justin K. Thannhauser Collection (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1978), p. 63.