ÉDOUARD MANET

Gill & Lagodich have framed five Edouard Manet paintings for museum permanent collections, they are shown here in chronological order.

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832–1883)

Fish (Still Life), 1864, oil on canvas, 29” x 36-3/8” framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Art Institute of Chicago in a period 19th-century French Neo-classical painting frame. “This imposing view of carp, red mullet, eel, oysters, lemon, stockpot, and knife is one of numerous still-life subjects that Edouard Manet painted in 1864, the year of his most intense engagement with the genre. Although the French translation of still life is nature morte (literally, “dead nature”), Manet’s painting seems very much alive. He achieved a sense of immediacy by strategically positioning elements—especially the precariously balanced knife and still-slithering eel—along the diagonal of the tablecloth, so that they seem to slide forward into the viewer’s space.” —Art Institute of Chicago, permanent collection label

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832 – 1883)

Bullfight, 1865/66, oil on canvas, 19 x 23-3/4 inches, framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Art Institute of Chicago; period 19th-century French Neo-classical painting frame, molding width 5-1/8 inches. “Edouard Manet’s trip to Spain in the fall of 1865 lasted only about 10 days, though it had a profound impact on him. In a letter to his friend the poet Charles Baudelaire, he described a bullfight he attended in Madrid as “one of the finest, most curious and most terrifying sights to be seen.” He made quick sketches there that informed several later canvases, including this one. Here he presented the moment of truth, as bullfighter and bull face one another, a gored horse lies dead or dying on the sand.” —Art Institute of Chicago, permanent collection label.

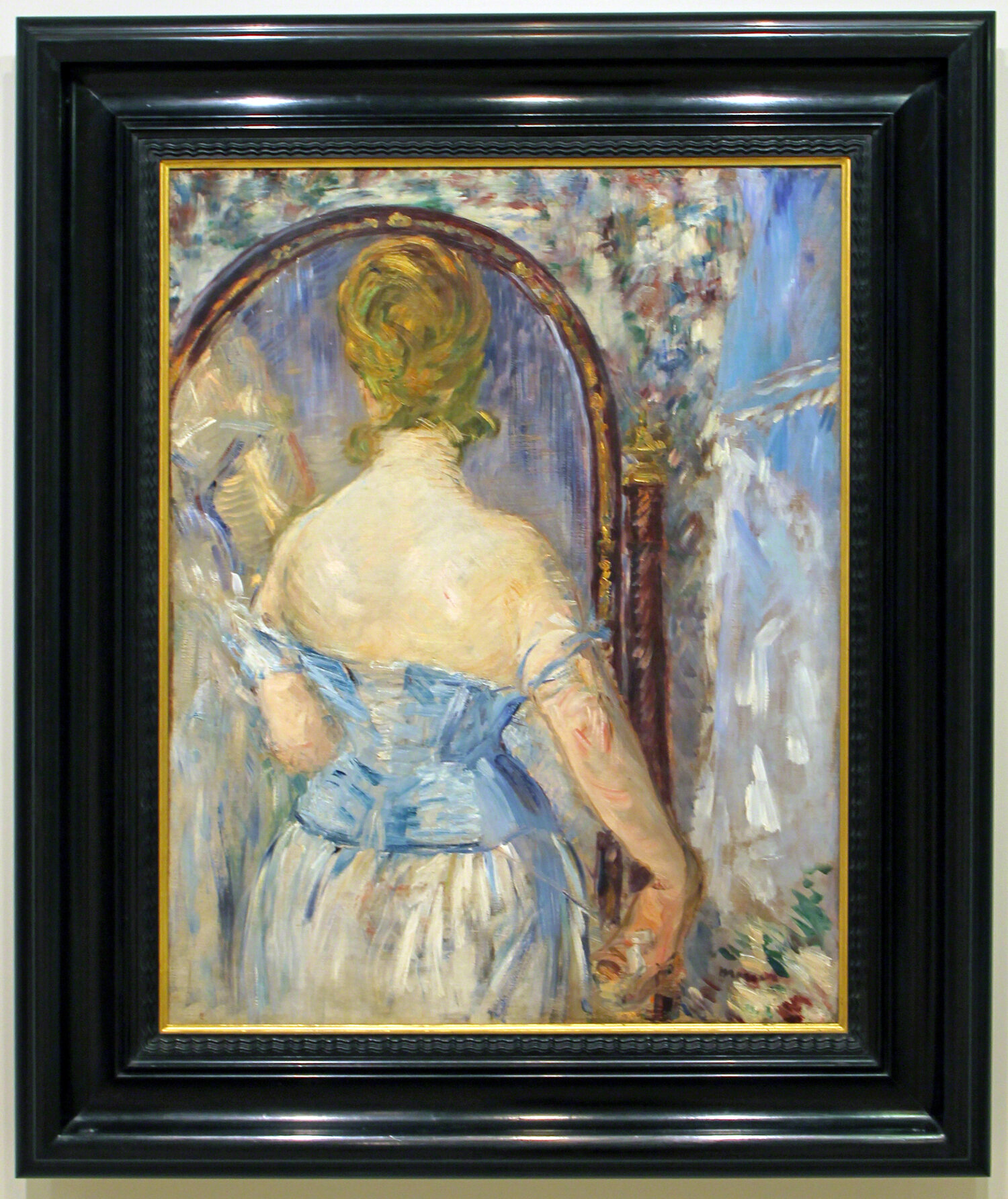

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832–1883)

Before the Mirror (Devant la glace), 1876, oil on canvas, 36-1/4 x 28-1/8 inches; late-19th-century Continental ebonized painting frame; dimensional molding with carved ripple and gilded hollow at sight edge; molding width: 6-5/16” "In 1865 Edouard Manet shocked Parisian audiences at the Salon with his painting Olympia (1863), an unabashed depiction of a prostitute lounging in bed, naked save for a pair of slippers and a necklace. While not an unpopular subject in 19th-century French painting, the courtesan had rarely been portrayed with such honesty. The artist provoked a similar scandal when his painting Nana (1877)—depicting a coquettish young woman in a state of partial undress powdering her nose in front of an impatient client—was exhibited in a shop window on the boulevard des Capucines. Manet’s attention to a motif conventionally associated with pornography reflected his desire to render on canvas the truths of modern life. It was a theme that symbolized modernity for many late-19th-century artists and writers, including Edgar Degas and Emile Zola, who devoted their work to realistic portrayals of the shifting class structures and mores of French culture. Images of courtesans may be found throughout Manet’s oeuvre; Before the Mirror is thought to be one such painting, related iconographically to Nana, but more spontaneous in execution. The artist’s vigorous brushstrokes lend an air of immediacy to the picture. As in Nana, the corseted woman represented here admires her reflection in a mirror; but this particular scene is extremely private—the woman, in quiet contemplation of her own image, is turned with her back to the viewer." —Nancy Spector. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832 – 1883)

Woman in Striped Dress, ca. 1877–80, oil on canvas, 69 1/8 x 33 3/16 inches (175.5 x 84.3 cm), framed by Gill & Lagodich, custom-made replica variation of c. 1900 French reverse profile painting frame gilded and toned to harmonize with painting: patinated 18.4 karat French Dauvet vert fonce gold leaf on varied bole and gesso substrate on applied cast ornament; patinated mahogany reverse; molding width: 5-1/4” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978 “In 1865 Edouard Manet shocked Parisian audiences at the Salon with his painting Olympia (1863), an unabashed depiction of a prostitute lounging in bed, naked save for a pair of slippers and a necklace. While not an unpopular subject in 19th-century French painting, the courtesan had rarely been portrayed with such honesty. The artist provoked a similar scandal when his painting Nana (1877)—depicting a coquettish young woman in a state of partial undress powdering her nose in front of an impatient client—was exhibited in a shop window on the boulevard des Capucines. Manet’s attention to a motif conventionally associated with pornography reflected his desire to render on canvas the truths of modern life. It was a theme that symbolized modernity for many late-19th-century artists and writers, including Edgar Degas and Emile Zola, who devoted their work to realistic portrayals of the shifting class structures and mores of French culture. Images of courtesans may be found throughout Manet’s oeuvre; Before the Mirror is thought to be one such painting, related iconographically to Nana, but more spontaneous in execution. The artist’s vigorous brushstrokes lend an air of immediacy to the picture. As in Nana, the corseted woman represented here admires her reflection in a mirror; but this particular scene is extremely private—the woman, in quiet contemplation of her own image, is turned with her back to the viewer. Manet’s endeavor to capture the flavor of contemporary society extended to portraits of barmaids, street musicians, ragpickers, and other standard Parisian “types” that were favorite subjects of popular illustrated literature. Since the subject of Woman in Striped Dress is unidentified—conjecture that she might be the French actress Suzanne Reichenberg remains purely speculative—it is tempting to view this portrait as Manet’s rendering of one such type: the fashionable Parisian bourgeois woman, complete with Japanese fan. Both paintings exemplify Manet’s use of seemingly improvised, facile brushstrokes that emphasize the two-dimensionality of the canvas while simultaneously defining form and space. From our vantage point, it is less Manet’s choice of subject matter than the tension between surface and subject, in which the paint itself threatens to dissolve into decorative patterns, that defines his work as quintessentially Modern.” —Nancy Spector

ÉDOUARD MANET (1832–1883)

Liserons et Capucines (Morning Glories and Nasturtiums), 1881, oil on canvas, 38-1/2 x 22-3/4 inches. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the McNay Art Museum. Custom-made frame, milled from thick soft maple, mitered construction with hollow on back edge, hand stained and oxidized finish; molding width 3-1/2” This frame is a darker variation on two frames in Musée d’Orsay on Henri Cross, L’air du Soit, and Matisse, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, and on the version we made for Guggenheim NY, Georges Braque, Landscape Near Antwerp, (without upper spandrel corners). Painting: Gift of Margaret Batts Tobin