RITMAN – RIVERA – ROESEN – ROBINSON – RUSSELL – RYDER

Please check this page again as we continue to update with more artists framed by Gill & Lagodich in both period and replica frames.

Artists are listed alphabetically.

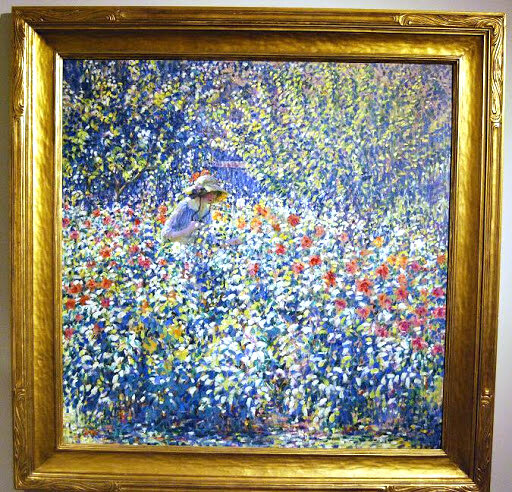

LOUIS RITMAN (1889–1963)

Flower Garden (Jardin de Flores), c. 1913, 39-1/2" x 39-1/2", oil on canvas. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Phoenix Art Museum. Period c. 1910 American Arts & Crafts painting frame; Newcomb-Macklin makers; gilded carved wood, molding width 5-1/4 inches "An American who studied traditional, academic art in Paris, Ritman turned his attention to modernism, becoming part of the third-wave of Impressionist artists. He worked in the scenic area of Giverny, France, painting in the gardens made famous by Claude Monet. Ritman’s paintings combine the decorative pattern of the Post Impressionists with the atmospheric effects of light that preoccupied the Impressionists in a style often called “decorative Impressionism.” This particular work is believed to have been displayed in the 1913 annual exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts." — Painting, gift of Mr. and Mrs. John M. Redfield, Jr., 1996.259.

DIEGO RIVERA (1886–1957)

La Ofrenda (The Offering), 1931, oil on canvas, 48-3/4” x 60-1/2” Framed by Gill & Lagodich for Art Bridges. Custom-made replica, c 1940s American frame, matte black painted finish on wood, molding width 5-3/8” “Amid a backdrop of verdant botanical life, three figures gather at an altar to honor the dead. Rivera’s scene depicts el Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead), a Mexican celebration in which the deceased are invited to commune with the living through an altar set with welcoming offerings. The composition of La Ofrenda creates an implied ring that connects the figures to the altar, suggesting the circle of life that unites the living with the dead. After the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), Rivera was invested in Mexico’s cultural revitalization. The artist’s passionate respect for the splendor and resilience of Indigenous Mexican culture is evident here. A garland of marigolds, omnipresent in Día de los Muertos celebrations, and symbolic of life’s exquisite fragility, is draped across a nopal cactus, which represents survival and appears on Mexico’s coat of arms. La ofrenda reflects the beauty and cultural endurance of post-revolution Mexico, demonstrating Rivera’s belief that “the artist is a direct product of life ... and a reflector of the aspirations, the desires, and the hopes of his age.”” —Art Bridges didactic label Credit line: Art Bridges AB.2017.19

SEVERIN ROESEN (c.1816 – c.1872)

“An Abundance of Fruit”, 1860, oil on canvas, 25 x 30 inches. Framed for the Art Institute of Chicago by Gill & Lagodich. Period c. 1850s American painting frame; gilded applied composition ornament on wood; molding width: 5 inches. AIC Americana Fund, 2004.2

CHARLES MARION RUSSELL (1864–1926)

“In the Enemy's Country,” 1921, oil on canvas, 24 x 36 in. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum. Period frame, c.1910 American Arts & Crafts frame, Newcomb-Macklin makers, hand-carved wood, original Roman-gilded finish, molding width 5-3/4 in. “Russell tried to keep himself separate from modernization as it crept into Montana, and he lamented the loss of the heroic Old West. His primary interest in art was the celebration of what he called “The West That Has Passed.” The scene in this painting is imaginary, inspired by a nostalgic vision set well before Russell’s time. To make the image look and feel real, Russell relied on his personal experience and observations from his early years in Montana. He also made annual trips to Indian reservations in Montana to brush up on his techniques and refresh his imagery. Russell’s paintings often bear evidence of a story—hints about what might have happened before or what might follow. When this painting was first exhibited, it was described as a group of Kootenai Indians crossing into another tribe’s territory to hunt buffalo. Because they have entered a hostile area, the Kootenai must travel carefully to avoid conflict. The men walk beside their horses and place buffalo hides, fur side up, on the horses’ backs. When viewed from a distance, the group looks like a small band of buffalo, which kept them from being bothered.” —museum label. Painting Gift of the Magness Family in memory of Betsy Magness

ALBERT PINKHAM RYDER (1847–1917)

The Essex Canal, c. 1896, oil on canvas mounted on board, 16-5/16 x 20-1/4 in. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Art Institute of Chicago. Period c. 1880s-90s American painting frame, gilded applied composition ornament on wood, wide gilded oak frieze, molding width 6-3/8 in. "Albert Pinkham Ryder was one of the most innovative artists of the late 19th century, creating reductive, yet expressive compositions out of thick, slowly worked paint, combined with glazes, varnishes, and unconventional materials. In The Essex Canal, a waterway faintly meanders from the green-hued foreground to a skim of blue along the horizon, with an expansive sky beyond. A younger generation of American artists celebrated Ryder as an important early modernist, who pushed toward abstraction and focused on the arduous process of painting itself as instrumental to one’s creative vision. Ryder’s reclusiveness only added to his intrigue and mythic status as an artist ahead of his time.” — AIC permanent collection label. Painting Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Geist, 1980.279

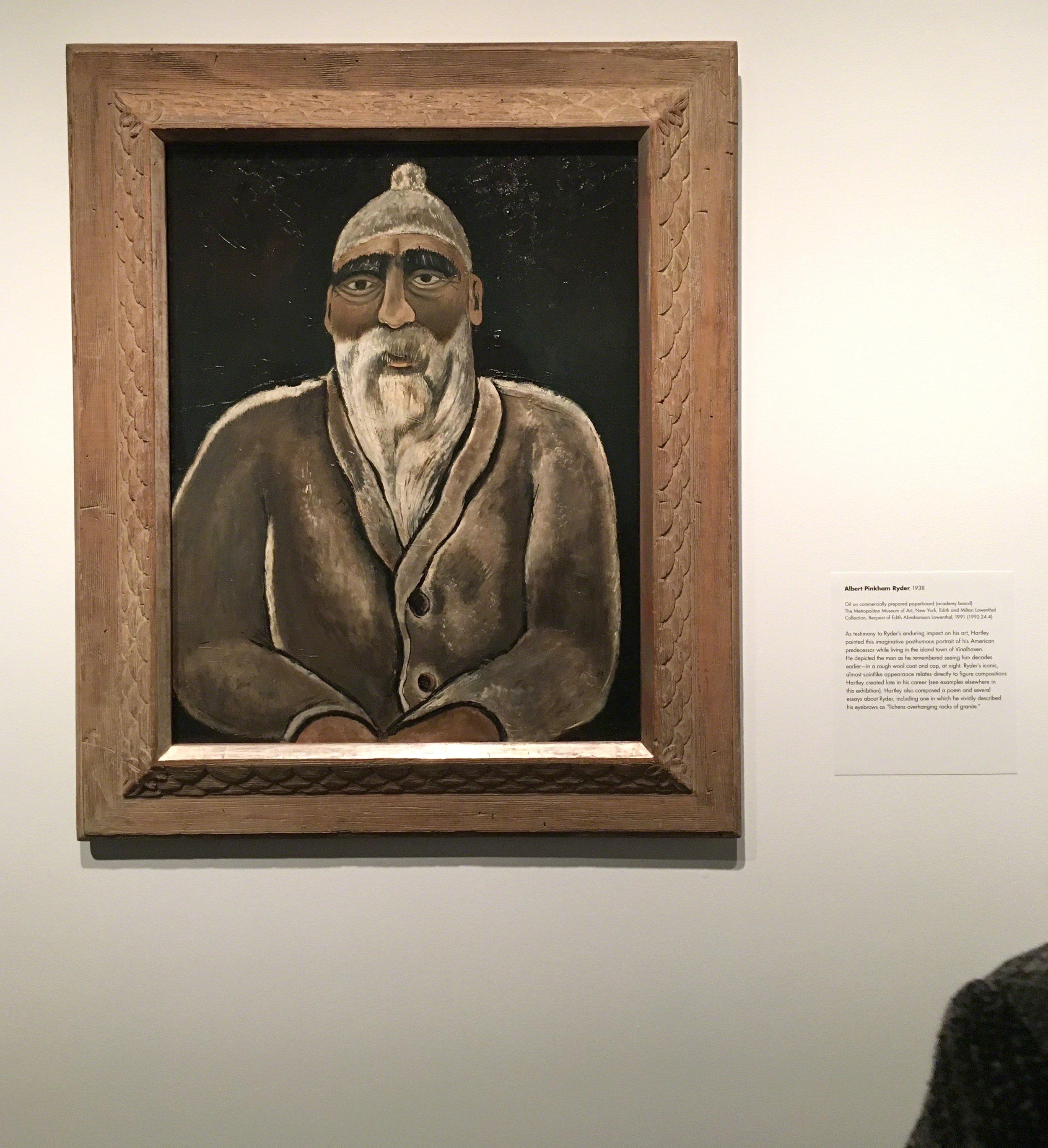

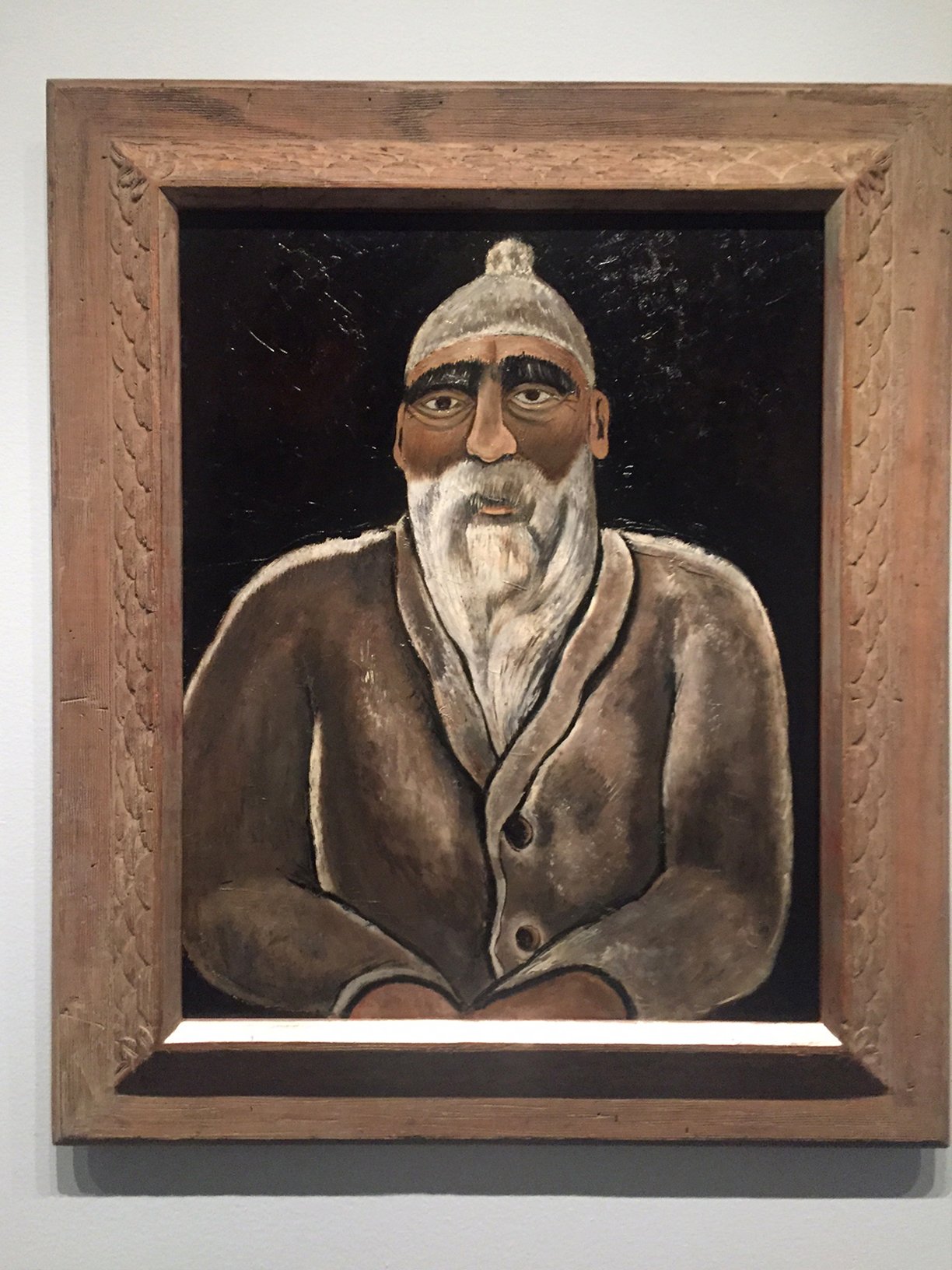

MARSDEN HARTLEY (1877–1973)

Portrait of Albert Pinkham Ryder, 1938, Oil on Masonite, 28 x 22 in. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. c. 1930s American Modernist painting frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers; silver-gilded beveled sight edge, wormy chestnut reverse profile, molding width 4-3/8 in. Previously on view at the Met Breuer in the stellar exhibit “Marsden Hartley’s Maine”, March 15 – June 18, 2017, and at Colby College Museum of Art, July 8 – November 1, 2017. “Having painted a series of dark landscapes inspired by the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder in 1909, Hartley returned to his American artistic hero late in his career. This highly imaginative portrait of Ryder is Hartley’s posthumous tribute to the painter, whose isolated, melancholy existence and financial poverty struck a sympathetic chord in him. In the portrait, Ryder appears frontal and isolated, like a saint or an icon. Hartley also composed a poem and several essays about the artist, including one in which he describes Ryder’s eyebrows as ‘lichens overhanging rocks of granite.’” —Met Museum label